Solanum tuberosum. Or, rather, a potato.

In this first unit for Food For Thought, we learned about the history of food, and how food has traveled across the world. For this Action Project, we were asked to take on the persona of a food from our families' history, and write an autobiography of sorts about it. I chose the potato. Below is the audio for my autobiography, as well as the presentation that goes along with it.

I am the humble potato. Today, I am the 5th most important crop worldwide. I originated in South Peru, in the Andes Mountains. I was first domesticated by the pre-Inca people of the Andes about 8,000 years ago. I was an originally toxic plant, but over time Andean and European humans domesticated me so that I became harmless. The first Spaniards in the region—the group led by Francisco Pizarro, who landed in 1532—noticed Indians eating these strange, round objects and emulated them, often reluctantly.

Within three decades, Spanish farmers as far away as the Canary Islands were exporting me to France and the Netherlands, which were then part of the Spanish empire. The first scientific description of me appeared in 1596, when the Swiss naturalist Gaspard Bauhin awarded me the official name of Solanum tuberosum.

European farmers were reportedly intrigued and mystified by me. King Louis XVI and nutritional chemist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier of France championed me to their famine-starved people. I was Europe’s solution to their food crisis. Many modern humans believe that my arrival in northern Europe spelled an end to famine. More than that, the historian William H. McNeill has argued that: “By feeding rapidly growing populations, I permitted a handful of European nations to assert dominion over most of the world between 1750 and 1950.” I, in other words, fueled the rise of the West.

In Ireland, I was something of a mixed blessing. I provided a cheap bounty of nutrition to a rural population in a land that had often struggled with its food supply, and helped fuel a population boom by improving public health. I helped the economy, too, by freeing up more grain for export. But, as more and more people came to rely on me as a principal food source, the stage was set for a national tragedy. Ireland came to rely so heavily on me for food that a rapidly spreading blight decimating me caused one of the deadliest famines in history.

I was introduced to the United States several times throughout the 1600s but not widely grown for almost a century until 1719, when I was planted in Londonderry, New Hampshire, by Scotch-Irish immigrants, and from there I spread across the nation. In Bangladesh, I have become a valuable winter cash crop, while potato farmers in southeast Asia have tapped into exploding demand from food industries. In China, agriculture experts have proposed that I become the major food crop on 60 percent of the country's arable land, and say a staggering 30 percent increase in yields is within reach.

Back in the Andes, where it all began, the Government of Peru created in July 2008 a national register of Peruvian native varieties of me, to help conserve the country's rich heritage, involving me. That genetic diversity, the building blocks of new varieties adapted to the world's evolving needs, will help write future chapters in the story of Solanum tuberosum.

I am important to the Havens family because they have used me in many a recipe in the past. They are a mix of Swedish, Irish and English heritage. Will’s mother’s family were midwest farmers, real “meat and potato” eaters. Even if the young one called Will does not particularly like me, his great-aunt “was the best cook in the family and always made scalloped potatoes.” This dish has nothing to do with scallops, it’s actually a casserole dish which contains thin slices of me, milk or cream, and cheese. This casserole was usually eaten at Will’s mother’s family potlucks. The family currently purchases me at a nearby Whole Foods Market. I got there though container transport by railway, most likely from Idaho. The current generation of the family doesn’t seem to like scalloped potatoes, however.

The humble potato (Solanum tuberosum) originated in the Andes mountains. It was first domesticated by the ancient Incas 8,000 years ago. The Incas found a way to eat the originally-toxic potatoes; by dipping them in a mixture of clay and water, it nullified the effects of the poison.

In conclusion, I thought that this project was quite difficult. I struggled with time management, and honestly, I didn't really like it very much. The first-person view was a bit silly to me. I still learned a lot about the history of the potato, and food trade.

“How the Potato Changed the World.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Nov. 2011, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-the-potato-changed-the-world-108470605/.

I am the humble potato. Today, I am the 5th most important crop worldwide. I originated in South Peru, in the Andes Mountains. I was first domesticated by the pre-Inca people of the Andes about 8,000 years ago. I was an originally toxic plant, but over time Andean and European humans domesticated me so that I became harmless. The first Spaniards in the region—the group led by Francisco Pizarro, who landed in 1532—noticed Indians eating these strange, round objects and emulated them, often reluctantly.

Within three decades, Spanish farmers as far away as the Canary Islands were exporting me to France and the Netherlands, which were then part of the Spanish empire. The first scientific description of me appeared in 1596, when the Swiss naturalist Gaspard Bauhin awarded me the official name of Solanum tuberosum.

European farmers were reportedly intrigued and mystified by me. King Louis XVI and nutritional chemist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier of France championed me to their famine-starved people. I was Europe’s solution to their food crisis. Many modern humans believe that my arrival in northern Europe spelled an end to famine. More than that, the historian William H. McNeill has argued that: “By feeding rapidly growing populations, I permitted a handful of European nations to assert dominion over most of the world between 1750 and 1950.” I, in other words, fueled the rise of the West.

In Ireland, I was something of a mixed blessing. I provided a cheap bounty of nutrition to a rural population in a land that had often struggled with its food supply, and helped fuel a population boom by improving public health. I helped the economy, too, by freeing up more grain for export. But, as more and more people came to rely on me as a principal food source, the stage was set for a national tragedy. Ireland came to rely so heavily on me for food that a rapidly spreading blight decimating me caused one of the deadliest famines in history.

I was introduced to the United States several times throughout the 1600s but not widely grown for almost a century until 1719, when I was planted in Londonderry, New Hampshire, by Scotch-Irish immigrants, and from there I spread across the nation. In Bangladesh, I have become a valuable winter cash crop, while potato farmers in southeast Asia have tapped into exploding demand from food industries. In China, agriculture experts have proposed that I become the major food crop on 60 percent of the country's arable land, and say a staggering 30 percent increase in yields is within reach.

Back in the Andes, where it all began, the Government of Peru created in July 2008 a national register of Peruvian native varieties of me, to help conserve the country's rich heritage, involving me. That genetic diversity, the building blocks of new varieties adapted to the world's evolving needs, will help write future chapters in the story of Solanum tuberosum.

I am important to the Havens family because they have used me in many a recipe in the past. They are a mix of Swedish, Irish and English heritage. Will’s mother’s family were midwest farmers, real “meat and potato” eaters. Even if the young one called Will does not particularly like me, his great-aunt “was the best cook in the family and always made scalloped potatoes.” This dish has nothing to do with scallops, it’s actually a casserole dish which contains thin slices of me, milk or cream, and cheese. This casserole was usually eaten at Will’s mother’s family potlucks. The family currently purchases me at a nearby Whole Foods Market. I got there though container transport by railway, most likely from Idaho. The current generation of the family doesn’t seem to like scalloped potatoes, however.

|

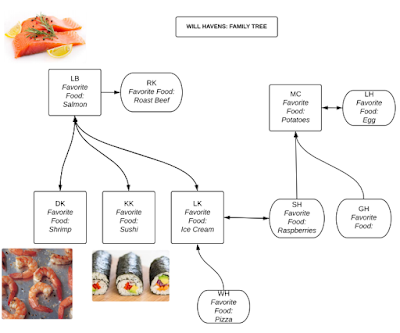

| WH, 2018, Family Tree |

In conclusion, I thought that this project was quite difficult. I struggled with time management, and honestly, I didn't really like it very much. The first-person view was a bit silly to me. I still learned a lot about the history of the potato, and food trade.

Works Cited:

“Diffusion.” The Potato: Diffusion - International Year of the Potato 2008, www.fao.org/potato-2008/en/potato/diffusion.html.

Fiegl, Amanda. “A Brief History of the Potato.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 17 Mar. 2009, www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/a-brief-history-of-the-potato 54839408/#JqxqeaBpXm5lbkqm.99.

"Potato.". “Potato.” Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, Encyclopedia.com, 2018, www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/potato.

National Potato Council : Potato Facts, www.nationalpotatocouncil.org/potato-facts/.

“Potato.” The Columbian Exchange, thecolumbianexchange.weebly.com/potato.html.

Comments

Post a Comment